External Symbols

John Morton, Wikimedia Commons

Visual symbols exert a subtle and powerful influence on thinking. Whenever a new form of communication comes to dominate a society, certain types of thought and interaction will be emphasized at the expense of others, and will influence the contemporary culture more than others.

Once speech was established, it became possible for our ancestors to record ideas outside of human memory. This took the form, at first, of visual symbols, which extended the range of knowledge possessed by the group.

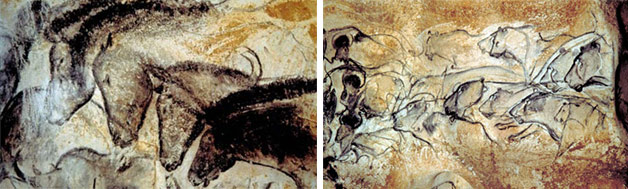

With few exceptions, ancient humans painted the same 32 geometric signs in caves all over Europe over a 30,000-year timespan. Paleoanthropologist Genevieve von Petzinger asks: What were they trying to say to each other—and to us?

Beginning with Art

Preliterate societies needed to express themselves in concrete ways. Art most likely served to connect them to their ancestors and the spirit worlds. It also helped to identify one community from another, establish territory and to plan and coordinate hunting.

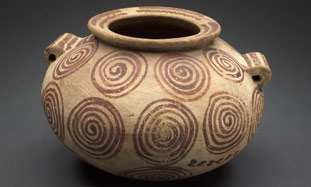

The spiral is repeatedly seen on the painted and engraved walls of the Upper Palaeolithic and on the decorated megalithic standing stones of the Neolithic period. The symbol’s persistence is thought to be attributable to it representing, among other things, an hallucinatory or trance state. Above left: Megalithic tomb of Newgrange, built around 3200 BCE. Above right: Egyptian jar (ca 3500–3050 BCE).

Effective communication requires that the parties share a common language, experience, and the mental models for interpreting that language. New ideas are not adopted in a vacuum: new symbols or mental models are typically based on those already established and familiar. Radically different notions are obscure and inaccessible to the culture or group.

Also, if a particular form of communication falls out of use, what we associate with it becomes lost and the culture or group no longer understands the meaning. The meanings behind the horses on the Chauvet cave walls, or the pillar humanoid forms at Göbekli Tepe are lost to us today, and we can only speculate as to their original significance.

Bridging the Gap between Speech and External Symbols

Written language lessened our dependence on past experiences, it enabled us to represent new ideas directly rather than to remind, embellish or duplicate the spoken word. It extended the common knowledge and experience of the group further into the future.

The alphabet is widely credited as dating back to about 1700 BCE based on its use by ancient peoples in the Sinai Peninsula and the lands of Canaan. The oldest complete sentence yet found dates from 1700 BC in the form of small letters on a hair comb made from elephant tusk. Its translation reads of a most human concern: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.” This comb was found in the ancient Canaanite city of Lachish in Israel. The comb was found in the part of the site holding palaces and temples and would have served as a prestige object to its owner.

Older examples from 1900–1800 BCE of alphabetic writing have been discovered in limestone cliffs above the Nile near Luxor. The alphabetic writing in a Semitic language enabled ancient scribes to write more simply and faster than would have been possible using the older hieroglyphics, because only 30 or fewer symbols were needed to encode a message compared to many hundreds of hieroglyphs. An interesting attribute noted by Idries Shah in his seminal work The Sufis is that “Arabic, the most precise and primitive of the Semitic languages, shows signs of being originally a constructed language.” Long before it was considered a holy tongue because of its association with the Qur’an, Shah points out that “It is built up upon mathematical principles—a phenomenon not paralleled by any other language.” The result of this conscious effort enabled the Sufis to utilize its basic concept groupings for initiatory or religious—as well as psychological—ideas, which they could collectively associate around a stem in a “seemingly logical and deliberate fashion.” Shah gives many examples of this phenomena in this invaluable book.

Another interesting fact is that the original letter qof on the Lachish comb, which corresponds to Q in the English alphabet, more closely resembles the image of a monkey with its tail than later Canaanite images. The modern English Q represents the body and tail of the monkey but the ancient qof letter also retains the monkey’s head atop the body-and-tail.

A precursor of Indus script writing may have been found on pottery fragments from the Early Harrapan period in present-day Pakistan that dates to 2800–2600 BCE, although too few fragments have been analyzed to establish whether the writing is alphabetic.

A counting system based on clay tokens was developed in Mesopotamia around 8500 BCE. The first known systems of writing, such as the Sumerian cuneiform, were pictographs and counting methods used in commerce between 4000 and 3000 BCE.

The use of a phonetic alphabet made written language more accessible to the general population, rather than restricted to an elite educated class.

From about the 9th century BCE the Phoenician adaptation of the alphabet and variants of it traveled around the Mediterranean, eventually giving rise to Greek, Anatolian and other scripts. In contrast to the more complex Cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs, it was the first script in which one sound was represented by one symbol, hence the name “phonetic.” In this form of writing, elements such as an “A” would have the same sound wherever they appeared, unlike hieroglyphic writing where each symbol was unique to its meaning and had to be learned by heart.

This new flexibility of representation made modern languages possible and accessible to many more people. It bridged the gap between speech and external symbols.

Unlike vocalization or speech, writing is not instinctual and not all cultures write, but where it did flourish, additional kinds of thought could be developed and expressed. Writing lends itself in particular to analytical and theoretical thinking, so it is not surprising that its advent coincided with an explosion of cultural and technological innovation.

The use of a phonetic alphabet made written language more accessible to the general population, rather than restricted to an elite educated class. During the golden age of Greek city-states between 500 and 300 BC, for instance, the great flowering of culture was stimulated by public study and discussion of ideas which were made accessible by an alphabetic written language.

Ideas Precede Symbols, Symbols Generate Ideas

When a symbol or symbolic system is introduced, it must identify something that the community recognizes, agrees upon and remembers before it can become a useful communication tool. But once it is in use it can have profound influences on the culture and generate new thoughts and new kinds of models.

The emergence of the numeric symbol for zero is a great example. Though humans have probably always understood the concept of “nothing” or of “having nothing,” it was not until the fifth century CE, when the explicitly expressed zero was used as a concise numeric notation in the Arabic number system, that mathematical “discoveries” and new ways of using numbers became possible. Having the symbol for zero enabled calculus, financial accounting, fast arithmetic computation, and even computers.

The important point to note is that the mental models we associate with words and phrases influence our thinking: they can both enrich and limit our interpretations, and sometimes with disastrous consequences.

The interplay between symbols and mental models within a group exerts a subtle and powerful influence on the thinking of its members. Whenever a new form of communication comes to dominate discourse in a society, certain types of thought and social interaction will receive focus at the expense of others. And those that are emphasized will influence the contemporary culture more than others.

Specific symbols are used for specific occasions and their power is particularly noticeable in times of perceived stress, as with Winston Churchill’s victory sign. A review of the history of the swastika, the most notorious symbol of that same period, can help us understand the potential power of external symbols.

The important point to note is that the mental models we associate with words and phrases influence our thinking: they can both enrich and limit our interpretations, and sometimes with disastrous consequences.

Today we are surrounded by logos, labels, titles and phrases all carefully tailored to describe the variety of activities undertaken by corporations and governments in the way they wish us to see them. When the United States government changed the name of one of its organizations from the “Department of War” to the “Department of Defense,” it was probably for the purpose of changing public perception from warlike associations (such as aggression, conflict, weapons, death, destruction and suffering) to defense-related ideals (such as home, family, justice, protection and liberty).

The First Word

The Search for the Origins of Language

Christine Kenneally

Human communication depends on the same genetic foundations as other animals. Some were born with a greater inclination to collaborate, forming the symbolic communication of language.

Numbers and the Making of Us

Counting and the Course of Human Cultures

Caleb Everett

Numbers, says Everett, are a key linguistic innovation that has distinguished our species and reshaped human experience.

In the series: The Evolution of Language

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

When Zero Was First Discovered

Marcus de Sautoy, Science Museum

Marcus de Sautoy, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford, reveals the vital importance of the Bakhshali Manuscript to the history of mathematics. Surviving leaf fragments from this birch bark scroll originate from the Indian subcontinent. They are over 1,800 years old and provide the first evidence to date of the invention of zero.

World: Middle East Oldest alphabet found in Egypt

BBC News

Scientists believe they have found the earliest surviving alphabet in ancient Egyptian limestone inscriptions and can trace its contribution to Greek.

Swastika: The Power of a Symbol

Human Journey

How a 5,000-year-old sacred symbol was acquired by Nazi Germany and imbued with the power to contribute to this ignominious period in human history.